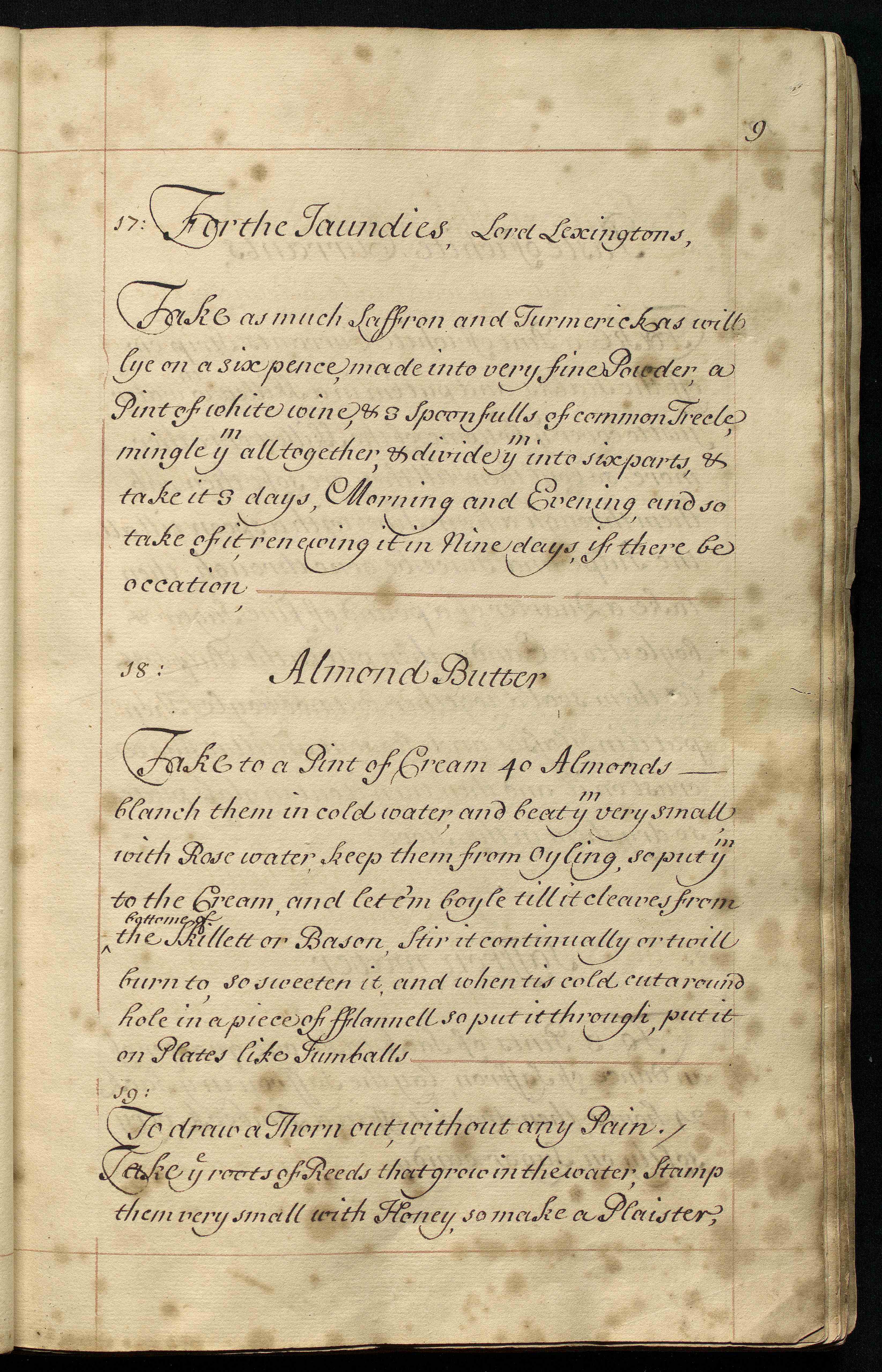

Like the first English manuscript cookbooks, nearly all the manuscript cookbooks compiled in the Anglophone world to the end of the nineteenth century contain both culinary and nonculinary material. In most books, the culinary recipes and the medical and household recipes are segregated from one another and this is true of most of the items in the collection of the New York Academy of Medicine. In Gemel book of recipes, 1660–1700, the nonculinary recipes are segregated from the food recipes by being written in separate clusters. In Recipe book, 1804; Recipe Book, circa 1830–1850; and Receipt book, 1848–circa 1885, the nonculinary recipes occur in a block at the end of book, after the culinary recipes. In Recipe book, 1700s; Cookbook, circa 1700s and 1800s; and Duncumb recipe book, 1791–1800s, the culinary and nonculinar y recipes are written from opposite ends of the notebook, a strategy often seen in this genre. In many manuscript cookbooks, the culinary recipes proceed from the front of the notebook and the nonculinary recipes are written from the back, the book having been turned upside down. This is the plan of Cookbook, circa 1700s and 1800s and Duncumb recipe book, although it is not carried out with consistency in either case. Recipe book, 1700s is atypical in that the nonculinary recipes are written from the front of the notebook, implying that they have precedence, and the culinary recipes are written from the back and are not inverted. The most complete segregation is achieved by the Hoffman author, who wrote her culinary and medical recipes in two separate books, Hoffman cook book, 1835– 1870 and Hoffman home remedies, 1775–1850. In the NYAM collection, only A collection of choise receipts, 1680–1700 proceeds without any apparent organizational plan, so that recipes for foods and wines are combined, jarringly, with remedies for tuberculosis and jaundice and formulas for brass cleaner and ink. Approved receipts in physick, 1650–1700 stands outside this discussion because it is not really a cookbook but rather a medical recipe book to which a small section of culinary recipes was appended by a later writer.

y recipes are written from opposite ends of the notebook, a strategy often seen in this genre. In many manuscript cookbooks, the culinary recipes proceed from the front of the notebook and the nonculinary recipes are written from the back, the book having been turned upside down. This is the plan of Cookbook, circa 1700s and 1800s and Duncumb recipe book, although it is not carried out with consistency in either case. Recipe book, 1700s is atypical in that the nonculinary recipes are written from the front of the notebook, implying that they have precedence, and the culinary recipes are written from the back and are not inverted. The most complete segregation is achieved by the Hoffman author, who wrote her culinary and medical recipes in two separate books, Hoffman cook book, 1835– 1870 and Hoffman home remedies, 1775–1850. In the NYAM collection, only A collection of choise receipts, 1680–1700 proceeds without any apparent organizational plan, so that recipes for foods and wines are combined, jarringly, with remedies for tuberculosis and jaundice and formulas for brass cleaner and ink. Approved receipts in physick, 1650–1700 stands outside this discussion because it is not really a cookbook but rather a medical recipe book to which a small section of culinary recipes was appended by a later writer.

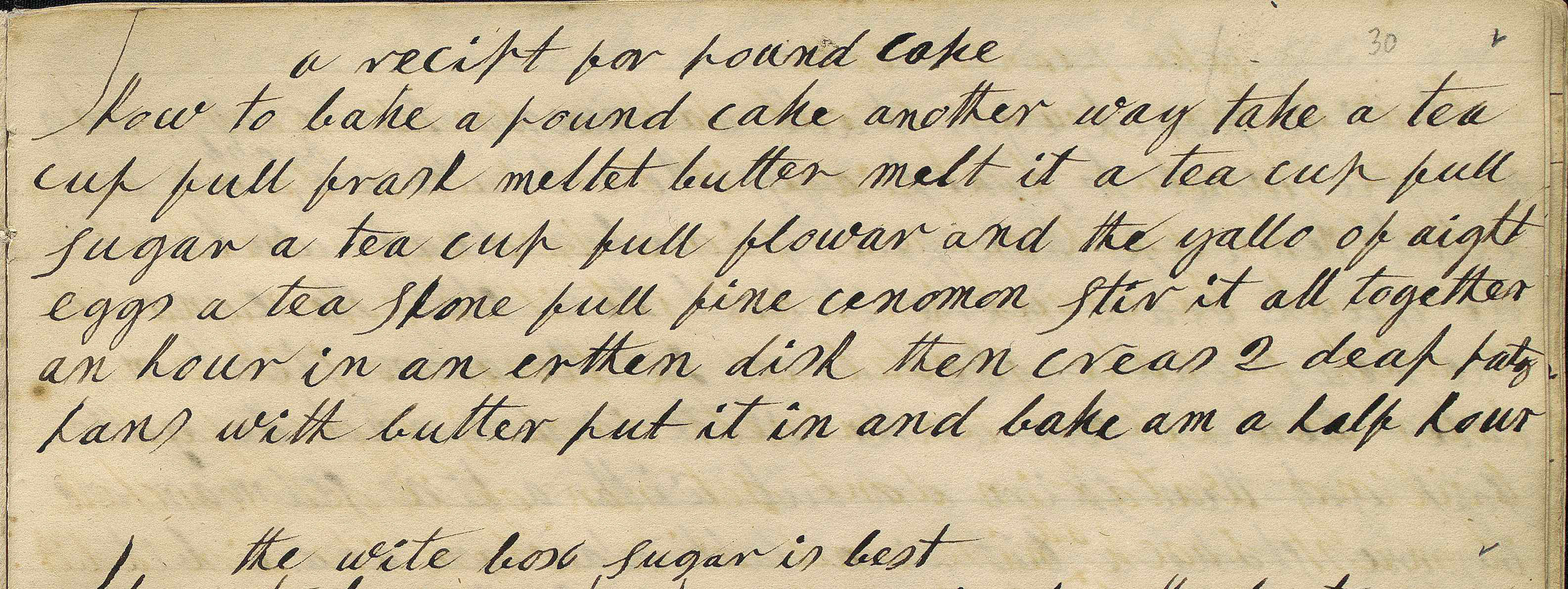

The Hoffman cook book in the NYAM collection is rare in that it unveils a style of cooking outside the mainstream norm. Written in halting English by a German immigrant to America, this highly interesting cookbook is composed primarily of German-inflected recipes like those we today associate with the so-called Pennsylvania Dutch. It also contains recipes for standard American dishes, such as roast turkey, pumpkin pie, and pound cake, but approached in idiosyncratic ways by a woman stru ggling to interpret a cuisine that was foreign to her. While the author of this cookbook was a cultural and linguistic outsider and her cooking outside the contemporaneous American mainstream, she was also a woman of privilege, a member of a prosperous German-American family that had owned paper mills in Maryland since the eighteenth century. For these reasons she was the sort of person, whether in Germany or America, who would be expected to use recipes and perhaps also to collect them.

ggling to interpret a cuisine that was foreign to her. While the author of this cookbook was a cultural and linguistic outsider and her cooking outside the contemporaneous American mainstream, she was also a woman of privilege, a member of a prosperous German-American family that had owned paper mills in Maryland since the eighteenth century. For these reasons she was the sort of person, whether in Germany or America, who would be expected to use recipes and perhaps also to collect them.

While manuscript cookbooks and printed cookbooks outline the same cuisine, broadly speaking, many manuscript cookbooks, perhaps regrettably from the point of view of culinary researchers, focus on only a part of it. Manuscript cookbook authors tended primarily to collect recipes for fruit preserves, fruit and flower wines, sweet dishes, cakes, and, after 1700, breads and cakes served at breakfast or with tea. Most printed cookbooks are more balanced, providing many recipes for meat, fish, and vegetable dishes and savory sauces as well as for the sweeter side of the repertory. Half of the manuscript cookbooks in the NYAM collection reflect the typical manuscript imbalance toward sweets. Most of the culinary and drink recipes in Gemel book of recipes and A collection of choise receipts are geared to banqueting, an extravagant repast of sweets that was sometimes served after important meals and sometimes staged as a stand-alone party during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Recipe book, 1700s titles its culinary section “Wines, Sweetmeats, & Cookery,” and recipes belonging, in a general way, to the former two categories far outnumber recipes for “cookery.” Two of the three culinary chapters in Recipe book, circa 1830–1850 are devoted to sweets. Receipt book, 1848–circa 1885, by an American woman named Jane Beck, can be aptly described as a cake cookbook. This imbalance can be explained, in part, by the fact that many ladies personally participated in preserve-making, distilling, and baking, while relegating the preparation of the principal dishes of dinner entirely to their cooks. In addition, the success of sweet dishes and cakes hinges on precise recipes, while savory dishes can be successfully executed intuitively, without recipes, at least by good cooks, or so people seem to have believed until the late nineteenth century. Finally, it bears mentioning that through the nineteenth century, the biggest per capita consumers of sugar in the world were the British, and American were not far behind.